Reaching the Apex

Stephen Tillery ’72 was trying to choose a religion. Not content to blindly follow family or friends, Tillery instead wanted to investigate the mysteries of the various theologies for himself. So he hopped on his bike and rode around Divernon, Illinois, interviewing Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian ministers, and even a Catholic priest. He peppered them with questions about what they believed, why it mattered, and why there were so many religions in the first place. The men of faith had to have been impressed. Tillery was only in sixth grade.

“That captures Steve perfectly,” says George Zelcs, Tillery’s friend and partner at the St. Louis-based law firm Korein Tillery and member of the Illinois College Board of Trustees. “He’s doing the exact same thing every day, asking people why things make sense to them and what their solutions are.”

Tillery is doing so as an internationally prominent attorney, litigating all types of complex cases from anti-trust to environmental to securities and to whistleblower protection. His firm has earned a worldwide reputation for fighting on behalf of the underdog against the corporate giants. In 2003, Tillery was lead attorney in a class action suit against tobacco goliath Philip Morris that resulted in a $10.1 billion verdict. He’s been nominated for Public Justice Trial Lawyer of the Year three times and written book chapters on trial practice. Korein Tillery has been named by the National Law Journal as one of the country’s top plaintiffs’ firms.

Before college, Tillery’s was more of an innate curiosity. His father was a machine mechanic, his mother a bank manager, both of whom stressed hard work and formal education as a means of advancement. But they also encouraged their son’s independent experiments. Tillery’s budding interests were vast, including theology, literature, and history, but like so many young boys and girls growing up during the Space Race of the 1960s, he was obsessed with science. He launched homemade rockets in the fields around his small-town Central Illinois home. He built a fractional distillation tower out of Folgers coffee cans and a grape fermentation station to show how wine is made (“It was also a nifty way for me and my friends to get a little wine,” he says with a grin). Tillery entered these projects in local science shows which were judged by college professors, including some from Illinois College. “The professors from IC were remarkable,” says Tillery. “They would stay with the kids for hours, not just testing our knowledge but making us feel good about what we had done and asking us if we had thought about trying this or that.” The experience was all Tillery needed to pick IC as his school — he didn’t apply anywhere else.

Tillery moved into Crampton Hall as a freshman in 1968. On campus, he encountered the same tight-knit, safe, and nurturing environment he had grown up in. IC was a community where students worked together rather than competed against one another. But that doesn’t mean it was easy. “My professors helped me not by being easy on me, but by being hard,” he says. “By being demanding, by raising expectations.” Tillery specifically remembers one French midterm on which he scored 98 percent. Rather than congratulating him, his professor, Dr. Carole Ann Ryan, gently reprimanded him on the four questions he got wrong — in her words “stupid mistakes.” “In other words, 98 percent was simply not enough,” he says. “That sent a clear message to me: She expected 100 percent accuracy.”

Less clear to Tillery was exactly what career he was striving toward. He piled on hours from nearly every page in the catalogue between working three jobs — running a language lab, washing trucks at a local farm supply business, and construction — that paid his way through four years of college. He indulged his interest in science, took heavy course loads in biology and psychology, which was to be his almost accidental degree when he graduated in 1972 as a member of the Phi Beta Kappa Society. He thought he wanted to be an academic, but quickly found that graduate school wasn’t for him. He thought maybe he’d like to try medical school, but discovered he had just missed the cutoff to take the MCAT entrance exam. It was December, and if he wanted to get into another graduate school the following year, there was only one test he could take, the LSAT for law school. And the last chance for that was three daysaway. With three days’ notice, zero preparation and a telegram to allow entry, Tillery took the grueling exam — and was immediately accepted into law school.

Fate was not finished with Tillery. After graduating from law school at Saint Louis University, he eventually took a job as an appellate lawyer with a private firm. After just two months, the firm’s two principal trial lawyers left the firm, leaving their caseloads essentially in the lap of Tillery, who had never tried a case in his life. He applied the work ethic he had learned at IC, reading every decision and opinion he could get his hands on, listening to hours of taped opening statements and closing arguments, learning step-by-step how to assemble evidence and use it to win a case. In his first full year as a trial lawyer, he tried 15 major cases to verdict — more than most lawyers do in an entire career.

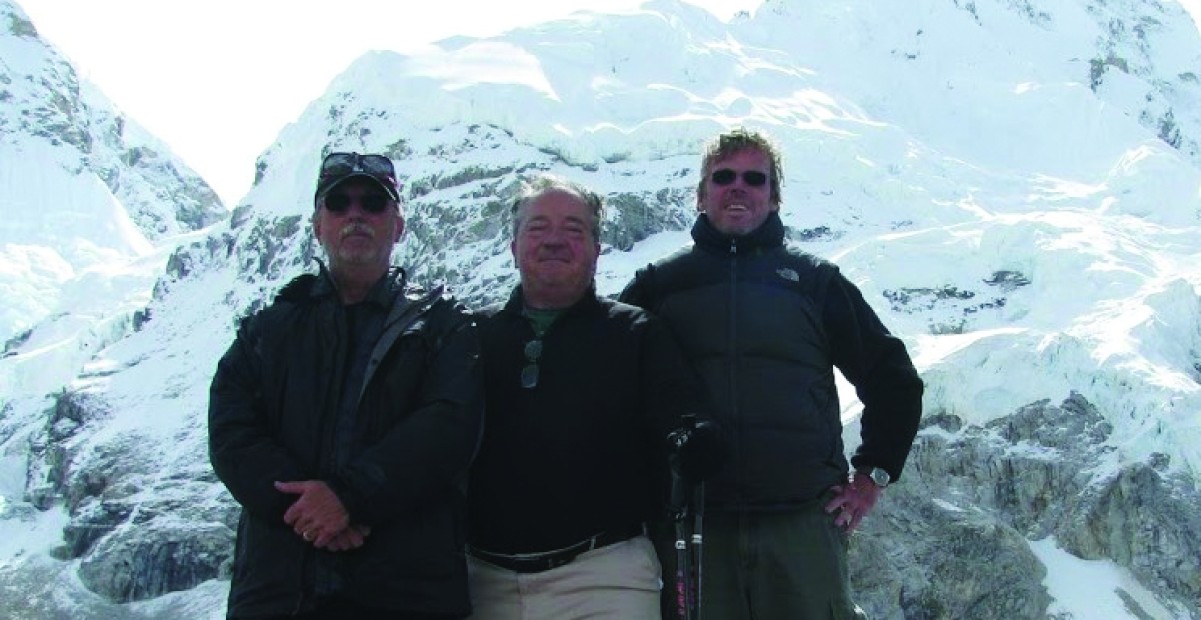

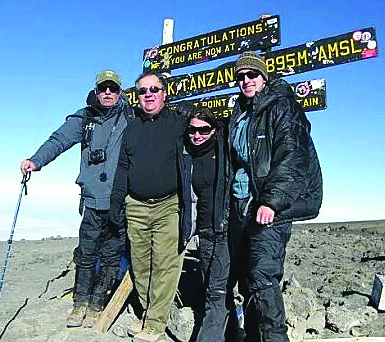

Some four decades later, Tillery has relied on this same work ethic to reach many apexes, whether it’s the 36th-floor executive office of his law firm overlooking downtown St. Louis or his newer interest in climbing higher peaks like Mount Everest and Mount Kilimanjaro. “I’ve never met a person who has as wide a range of intellectual and academic interests who is as fearless, ambitious, and dogged in pursuing something,” says Zelcs. “And yet you can tell from where he grew up, where he went to school, a small college. Somehow, despite all the incredible success, he has always managed to remember where he came from and who he is.” Tillery has given back in many ways, including support for Big Brothers Big Sisters of Southwestern Illinois and serving on the international board of a non-profit called Meds and Food for Kids, which has fed and saved thousands of malnourished children in Haiti.

Illinois College has also been the beneficiary of the Tillery family’s gratitude. Of particular note, he and Katherine Thompson Tillery ’74 established the Tillery Student-Faculty Collaboration Fund, which has brought students and faculty closer together to work side-by-side on research projects. This initiative has been instrumental in building Illinois College’s undergraduate research program in a way that promotes the collaborative spirit Tillery felt when going to school here. Many students have benefited from the Tillerys’ generosity, including students who have accompanied biology professors to Cuba to research ghost orchids and bats, and travelled to Madagascar to investigate orchid conservation. Last year, Tillery established a research fund for outstanding students and an award for prestigious post-graduate study in order to increase the number of students who will benefit from working closely with faculty mentors. These experiences and many others like them, will no doubt help students to achieve their dreams after they graduate.

“Steve Tillery has a strong loyalty to Illinois College,” says President Barbara Farley. “I am grateful to him for his deep and abiding commitment to building the College’s reputation for academic excellence. His ultimate goal is to help students excel so that they will be prepared to attend high-caliber graduate and professional schools.” Tillery was honored by Illinois College as a 2016 Distinguished Service Award recipient. This prestigious award recognized Tillery’s meritorious service to his alma mater, his intellectual pursuits and his service to humanitarian causes. In his acceptance remarks, Tillery spoke eloquently about the life-changing experiences he had at Illinois College.

“Clearly Steve recognizes that his education was a transformative thing in changing his life and the things he’s been able to do,” says Zelcs. “He believes everybody deserves the opportunity to better themselves through education and be whatever it is they’re best at doing. Everyone deserves that shot.”